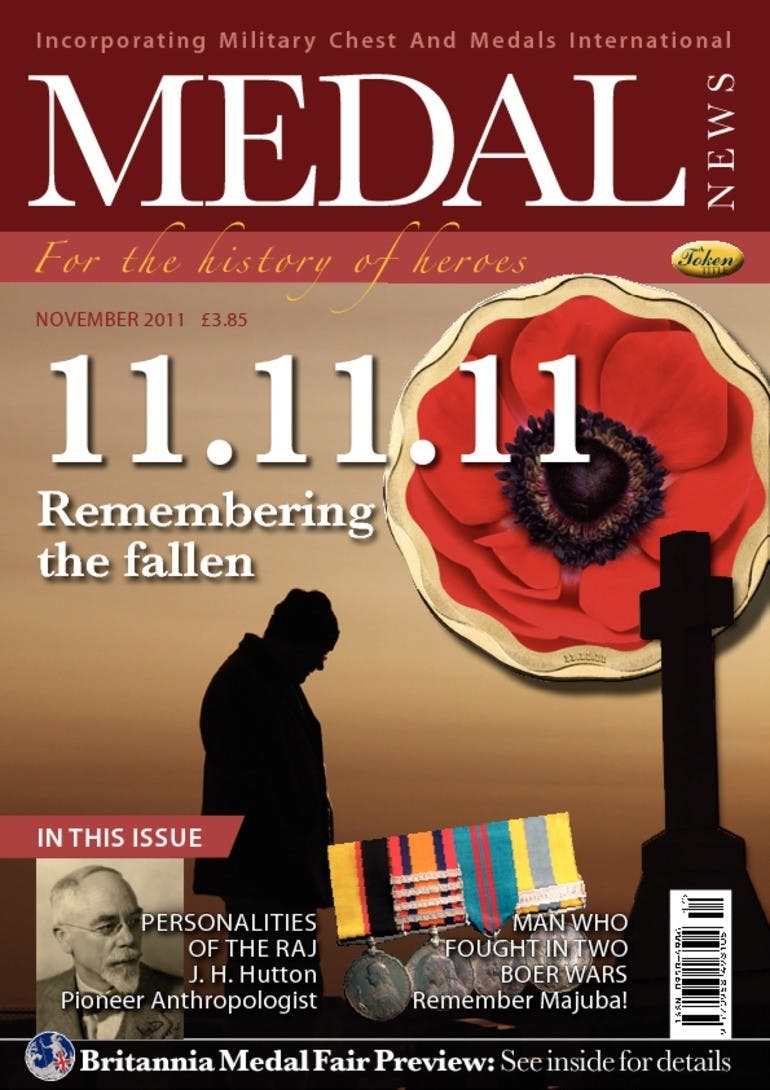

11.11.11

Volume 49, Number 10, November 2011

The Hollywood effect? THIS month’s Market Scene shows that the South Africa Medal to Rorke’s Drift defender Lance-Sergeant John Key of the 2/24th Foot sold for a whopping £28,800. In Warwick & Warwick’s December sale there are two Isandhlwana casualty medals on offer and they too will undoubtedly fetch large sums (they are estimated at £6,000 for the 1/24th Foot example to Pte T. Goss and £5,000 for the example named to Driver T. Clarke of the Royal Artillery—but will probably go higher). Now such “Zulu” medals have always commanded a premium, just as medals to Light Brigade chargers have, or those posthumously awarded to casualties who were killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, but I have never really understood why. Admittedly the Rorke’s drift medal is something special—the sheer heroism of such a small garrison defending its position against vastly superior numbers (who were not “simple tribesmen armed with spears” as some politically correct sections of the media would have us believe, but rather were trained and feared warriors who did have access to guns, British ones as it happens . . .) should command a premium and the small numbers of medals awarded perhaps justifies their price. They don’t, after all, come up that often. However, in the case of Islandhlwana there were over 1,300 men killed at that battle so rarity is not the main reason for the price, and even with the Charge of the Light Brigade there were famously over 600 who rode, so again these medals can’t really be called scarce and do come up for sale with reasonable regularity. The prices paid for first day of the Somme casualties are also hugely out of line with the availability of such medals and with over 19,000 killed or dying of wounds they certainly can’t be seen as rare. So why do all these medals still command such a premium? You will note, perhaps that the three cases I have highlighted are actually all considered military blunders. The defeat in 1879 probably occurred because the British Forces were split and certainly weren’t expecting the Zulu attack to come from where and when it did; the Charge at Balaklava is well documented as a military foul up and the First Day of the Somme cannot be considered by any to be anything other than a disaster for Britain and her allies. Is it because they were failures that they hold such a place in the heart of the medal collector? That hardly seems logical does it? After all, we collect gallantry medals too and they are the very epitome of military success and heroism and it seems unlikely that we would also want to celebrate apparent failure in the same way. But it seems we can’t get enough medals awarded to those who weren’t on the winning side in a particular battle. Gallipoli casualties are a good example—the whole Dardanelles campaign ultimately failed, yet medals to men who landed on the peninsular fetch much more at auction than medals to men of units that didn’t. Operation Market Garden is another case in point—medals awarded to men who fought in the famous campaign that went a “Bridge too far” also seem to far outstrip similar North West Europe medals, with the exception perhaps of D-Day itself which certainly command higher premiums than medals awarded to men in other theatres. Now I’m not suggesting that such premiums aren’t warranted—the market has found its own level on such things and who am I to argue? But it does puzzle me as to why that level has been found. Why, for example, do Heavy Brigade chargers, although eagerly sought after and collected, not fetch quite as much as those awarded to their Light Brigade counterparts? Surely medals awarded to those who took part in a successful charge should be more highly prized than those whose charge was less than successful, but apparently not. Perhaps the reason for this apparent disparity can be seen in what I term the Hollywood factor. With the exception of the first day of the battle of the Somme, which has an attraction for collectors all its own, the battles/engagements that seem to attract the huge premiums are those that have, at some time or another been given the Hollywood treatment and are therefore more recognisable to the average collector. Zulu Dawn with Peter O’Toole, Burt Lancaster and a galaxy of stars; Zulu with Stanley Baker and Michael Caine; Gallipoli with Mel Gibson; The Charge of the Light Brigade with Trevor Howard, John Gielgud, et al.; A Bridge Too Far with Michael Caine (again), Sean Connery, Edward Fox, Gene Hackman and many others—all have been watched and watched again many times by us collectors as we were growing up and the stories (with all their Hollywood inaccuracies) are firmly entrenched in our memories. They are part of our past and treasured as such and maybe this is why medals to these battles command the prices they do. It would certainly explain why those given for heroic encounters not committed to celluloid (such as the Battle of Bois des Buttes and the stand of the 2nd Devons in 1918, when over 500 officers and men, nearly the entire battalion, were either killed or captured, but their stand allowed the French to regroup—an action for which the battalion was awarded the Croix de Guerre) only fetch a high price when contested by two collectors “in the know”. If this is the case and the Hollywood factor has distorted medal prices then at least I know how to increase the value of my collection should I need to: I just have to write a good screenplay and get it accepted. Does anyone know a good agent . . . ?

Order Back Issue

You can order this item as a back issue, simply click the button below to add it to your shopping basket.