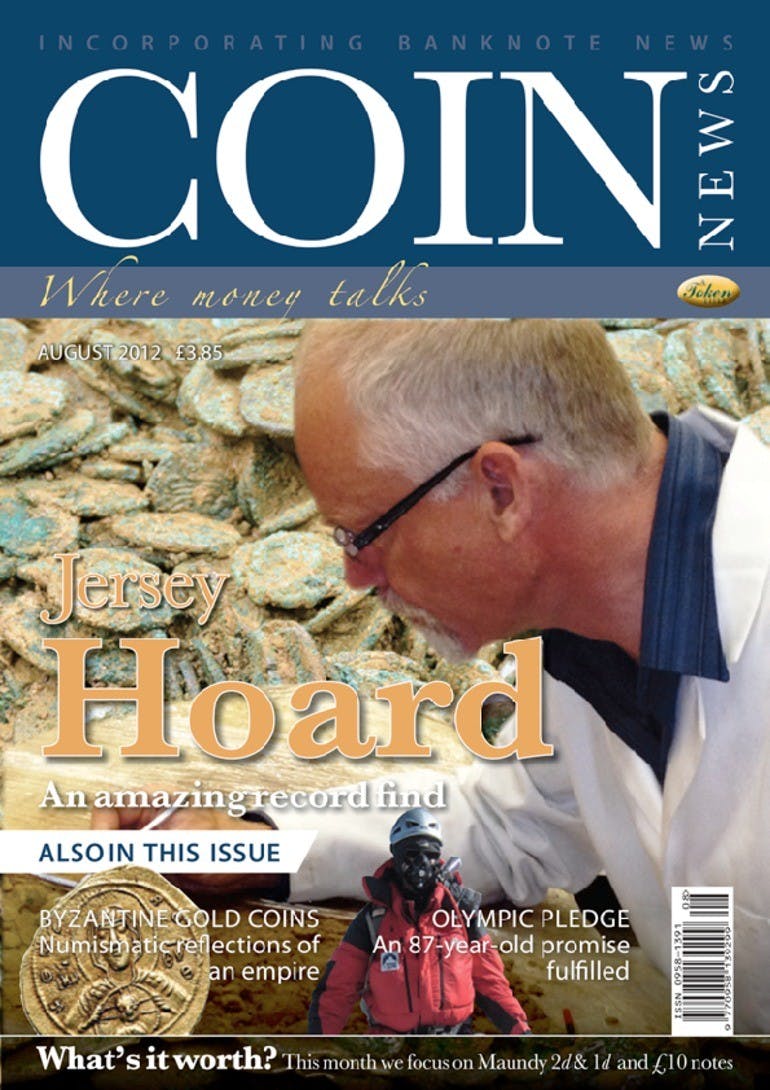

Jersey Hoard

Volume 49, Number 8, August 2012

A double-edged hoard THIS month’s issue features no fewer than three articles focusing on hoards (pages 33–34,45–48 and 55–56), so it is perhaps fitting that my “Comment” this month focuses on them too! It is, of course, every metal detectorist’s dream to uncover that elusive “hoard”, every numismatists dream to be able to gaze upon such a sight in situ and every collectors dream to be able to label his coin with the provenance “from the XXXX hoard”. A hoard is a wonderful sight to behold, of that there is no doubt, and even if you have only ever seen one in a museum as a cleaned up “re-enactment” of how it looked when discovered, there is still something particularly appealing about all those coins together. Often such an exhibit will include the remains of the pot that once held the coins, often there will be information about when, how and where they were discovered (although that latter information is never very detailed for obvious reasons, the museum doesn’t really want a lot of amateur archaeologists scouring the site), and always there will be conjecture as to why the hoard came to be buried in the first place. Theories regarding hoards abound—from the “religious offering” theory to the tried and tested “hiding it from the Vikings* (*insert barbarian name here to suit era)” and certainly any one of the theories (indeed all of them) may well be the real reason why the coins were buried only to be unearthed centuries later by a lucky treasure seeker. Certainly the idea that money was buried to keep it safe is a logical one but if you take something like the Jersey hoard (pages 33–34) with perhaps 50,000 coins in it and a weight of nearly three quarters of a ton it seems unlikely that it was hidden in haste nor indeed by one person or family! We will of course never really know why, every so often, large numbers of coins suddenly turn up in one place, nor indeed how many more such finds are just waiting to be discovered and that poses us collectors something of a problem. As you will know the reason certain coins fetch huge sums of money whilst others, seemingly the same, fetch very little is down to rarity—whether of date, mintmark, die flaw or anything else that sets them apart from their more everyday counterparts. But what if that rarity factor was taken away? Take the Coenwulf gold mancus (penny) for example—a “one off” discovered in 2001 by a footpath in Bedfordshire it fetched £230,000 at auction and was subsequently purchased by the British Museum in 2006 for nearly £360,000, making it the most expensive British coin at that time. It is reasonable to expect that should the museum ever need to sell that coin they could expect a similar return—but only if it remains a “one-off”. What happens if a hoard of them is discovered tomorrow? It is highly unlikely of course, but never say never, stranger things have happened and should such a discovery be made, then suddenly the value of the original has to be in doubt. Look at the 1933 American double eagle: in 2002 the only example outside the US institutions fetched $7.6 million— but would it have made that had the other ten now known to exist been discovered earlier? Such is the double-edged nature of a hoard (whether ten constitutes a hoard is open for debate—when you’re dealing in millions of dollars perhaps it is), they are a wonderful thing to find, fantastic to see but actually for collectors they can sometimes be a disaster. The “rarity” aspect is only one of the problems a hoard might throw up however, and its discovery will often lead to a number of questions—questions that split the numismatic and archaeological communities down the middle. For example, when a hoard is found should it be kept completely intact? Should all the coins discovered be kept together or should there be a chance for us collectors to get our hands on one or two of them? If the former then the issue of rarity doesn’t come into it, after all if the hoard is to be treated as a single item then there is no danger of individual coins getting out to dilute the market, but is that fair on collectors? Shouldn’t they all have a chance to own coins from a hoard? After all, often these coins have hitherto been difficult to get hold of—is it right that collectors are still denied the right to own one even though suddenly there are dozens, maybe hundreds to choose from? And why should a hoard be kept together anyway? After all, with something like the Jersey Hoard does it matter if 30,000 or 50,000 coins are exhibited (if that’s what is going to happen to it)? Who is going to count them? I suspect those who already own examples of coins found in hoards will err on the side of keeping a hoard intact, leaving their coins as rarities outside a museum, whereas those who aren’t lucky enough to own an example of the coins found will clamour for the hoard to be split – but is it that clear cut? Is there a right or wrong answer? I’m going to sit firmly on the fence on this one, knowing that no matter what my opinion is there will be some who vehemently disagree—I would love to know your viewpoint though.

Order Back Issue

You can order this item as a back issue, simply click the button below to add it to your shopping basket.